Serena Lee

Opposite Day

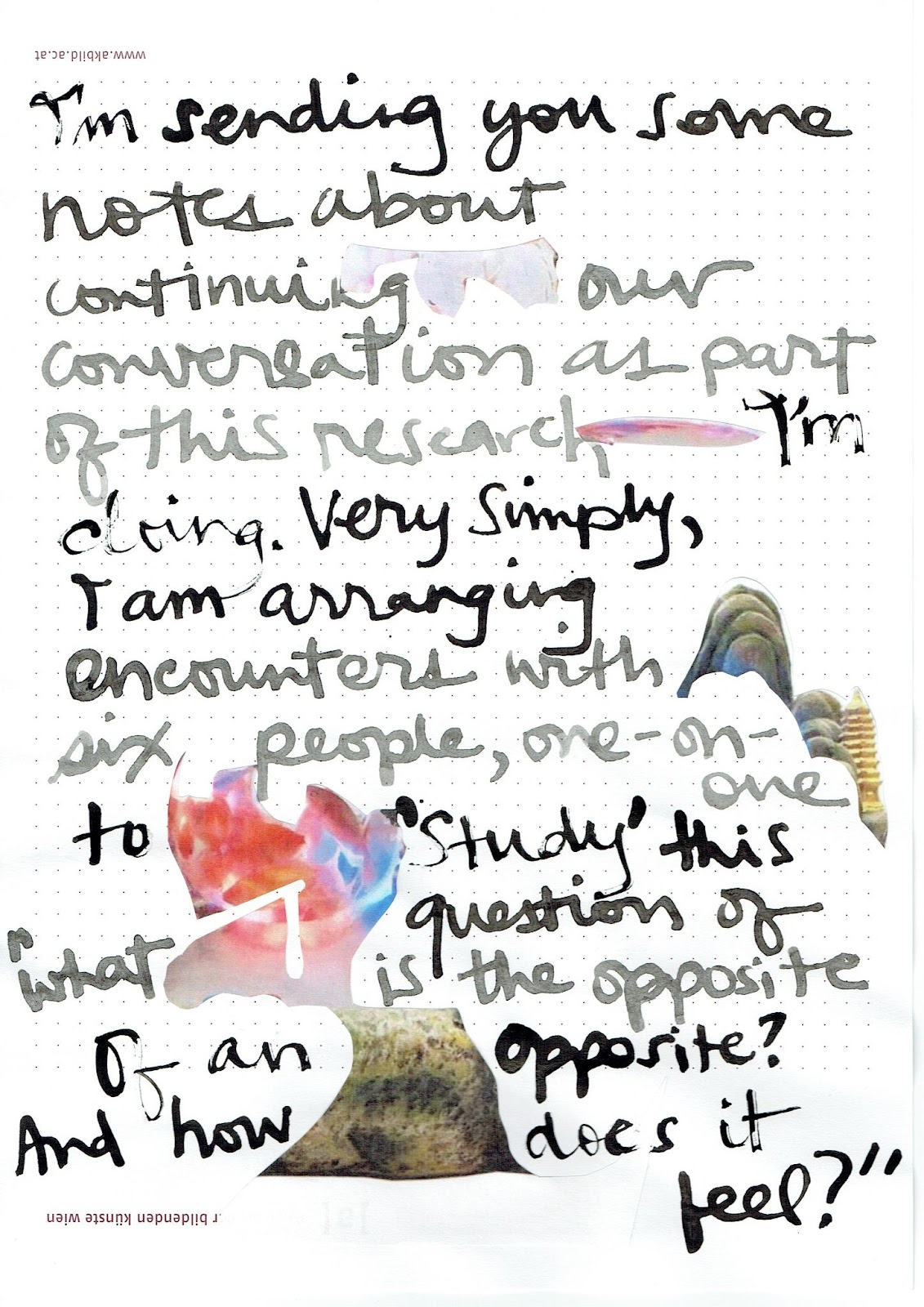

Opposite Day plays with notions of contradiction, separation, and dissonance. This conversation-based project winks at language and its limits through embodied study. Through a year-long series of one-on-one encounters, Serena Lee studied with artists, writers, and makers Alix Eynaudi, Leonardiansyah Allenda, Sameer Farooq, Giles Bailey, Ruthia Jenrbekova, Fan Wu, and Sanne Oorthuizen. We studied through reiki, visualizing meditations, drawing, (song) writing, walking, 氣功 qigong, and visiting museums. In November 2021, we convened The opposite of an opposite, a gathering that brought together these study partners and conversations, with a talk by complementary medicine practitioner, Lynn Teo, giving insights on 陰陽 yinyang as the operational logic of opposites.

“Let’s not call it an exhibition”

A conversation between Toleen Touq and Serena Lee

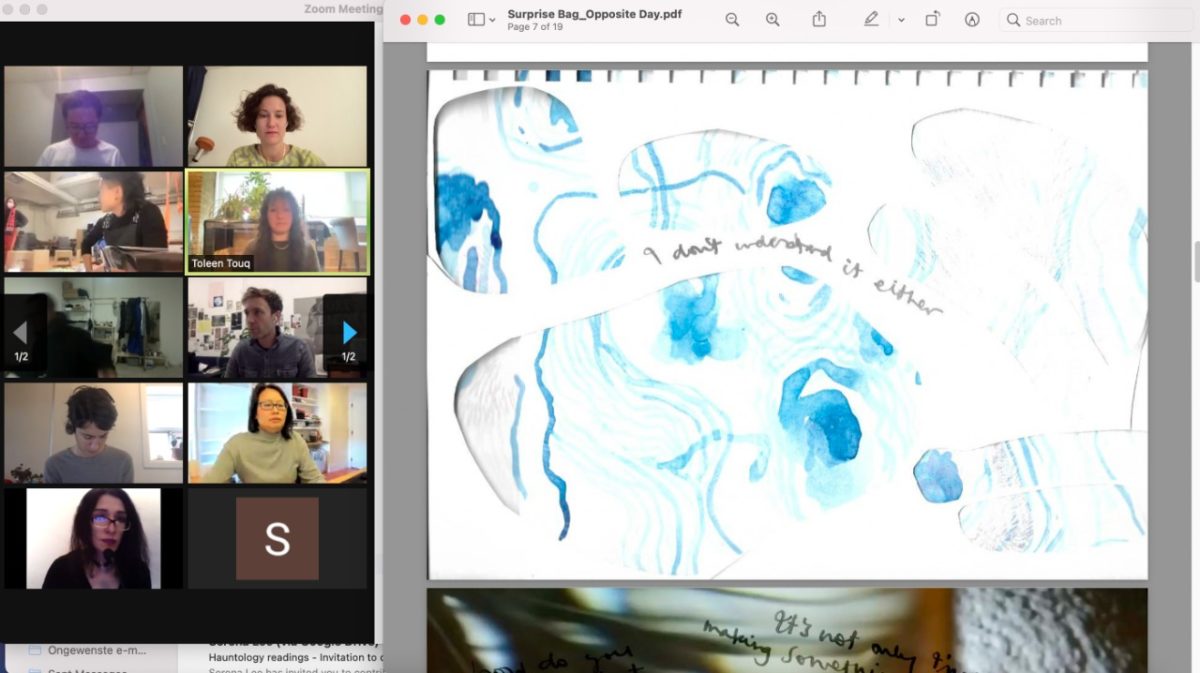

In parallel with and preparation for Serena’s project Opposite Day, Serena and I studied together over the course of most of 2020 and 2021. Through conversation, we thought through and with the ideas behind her project while also unpacking the material and sensory registers that stimulate both our practices. We read texts (see citations) and talked about how concepts of opposites, dualities, religion, temporality, and continuity, and practices of collaboration, embodiment, intuition, play, and music appear in our daily lives. We hurriedly took notes during and after dinners, walks in the countryside, and online meetings across different continents. This conversation below is a snapshot of one of our talks, recorded in March 2021. Admittedly, we both felt uneasy with the way recording shifts the way we talk, and unsettles the spontaneity of relating and bouncing ideas off of each other. Despite that, for me this was one of the most enjoyable and fruitful parts of Missed Connections; engaging with Serena and the other artists in prolonged conversation without a definitive goal in mind. The conversations were ends in themselves, and they continue to trickle over into collaboration, and friendship.

Toleen:

Let’s start this conversation by thinking about conversations. The conversational form is your method of study, your method of collaborating with people. What is it about the dialogic form that is important or fruitful for you? For me, part of the appeal is play and responsiveness to unexpected thoughts, words, or associations. Another part is building through conversation. When we talk regularly, we refer to things we said earlier, to things we’re reading or people we’re thinking of. But it’s hard to grasp or define the learning aspects of conversations. There’s the engagement during the conversation, and then there’s something that usually shows up at different moments after the conversation, right?

Serena:

I come back to the question: what does talking do in terms of learning? What is the relationship between what we know and what we can articulate? As Audre Lorde says: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”[1] To re-examine these tools – in particular, our words – is a fundamental discomfort that we need to experience. Since I’ve been reading across dao related writings translated from classical Chinese, I am in an unfamiliar place, and from here, questioning the particularity of how western thought uses words.

Toleen:

Unlearning Western epistemologies, or unlearning Western modes of thought…I don’t know if that’s possible without breaking down your use of language and specifically the use of the English language. I am taking a class with Dolleen Manning (Anishinaabe) right now and she talks about trying to articulate the mnidoo[2] – “spirit/mystery, potency, potential – in conversation with Western philosophers. For her, it’s a strategy to subvert the dominance of Western theories, to put Anishnaabe philosophy on the same level, despite the difficulty of articulating those concepts of mnidoo in the English language. She once mentioned that English also became the dominant language because it’s a dominating language.

Serena:

Western thought and Western culture privilege articulating with clarity and precision. In writing about the 易經 Yi Jing, François Jullien asks, does thinking necessitate questions?[3] Jullien writes that, with the Yi Jing, there’s no meaning to read into. It’s just a description of how things operate.

I’m intrigued by his argument that the drama of decoding and unwrapping meaning – this messianic relationship to meaning-making – is built into how we define truth by making arguments through words, in English and the languages of modernity/coloniality: they are grammatically equipped to dominate.

道可道,非常道。

名可名,非常名。

道德經

Which is something like:

Way that can be way-ed, is not the way.

Name that can be named, is not the name. – Dao De Jing

How can we study/know/think, with and without language?

How do we understand difference, through sense, through language?

What does it mean “to matter”?

What is the relationship between movement and meaning?

Toleen:

Back to your question of “what is talking doing in terms of learning,” what about things that can’t be clearly articulated?

Serena:

I think I’m becoming very comfortable with just following my gut, and not articulating when I don’t think it needs to be articulated.

Alix, while walking in Prater: “I’m very patient,”

Alix, while walking in Prater: “I’m very patient,”

Toleen:

I know you’re reluctant to call things “exhibitions”; it’s interesting what happens if you call something a “project” rather than an “exhibition.” “Project” has other kinds of connotations about beginnings and endings, processes, phases, and results, right? So if we’re saying this is not an exhibition, but this is something else, what would that do to the process of noticing, or of seeing the work and being with the work? Again, we’re circling back to the relationship of language to perception and experience.

Serena:

I think there’s this edge of things being vague and as precise as they need to be, but not fixed. How do we get to those relationships of being with words where you’re not rushed into meaning-making?

Toleen:

Because within Opposite Day, you and your study partners were working at different paces, but where you were consistently and constantly in conversation. You were working towards something, but not in this way that’s fixed as a goal within the conversation itself. And that makes me think, what happens to all these conversations after they’re “done”?

Serena:

What is ongoing study, right? These conversations were overlapping with wave hands, like clouds, not eyes [4] and those were always very much going to be ‘materialised’. Like the conversations with Vancouver-based collaborators Megan Hepburn and Gina Badger about creating scent gestures to be experienced in the space, and with Lee Su-Feh about taijiquan practice and diasporic experience, and all this other stuff. Yeah, there’s just no rush for it to be a thing.

Maybe what’s happened as well is that I’ve felt myself change my pace and reflect on my tone with some people more than others, which is neither here nor there. But with some people, like with Alix, when we were walking, it was a feeling of very deliberately slowing down. And not packing in words. Really just letting go of the need to talk, actually. That transfers over to being in conversation with the things around me, like the things that I’ve had for years, the things that I’ve just come across in the last paragraph, connecting with the things that I’ve been carrying with me for like the last ten years, you know? Carrying with me in dreams. Something that I keep going back to is my 公公’s (grandfather’s) house; I just had another dream about the house the other day.

“Opposite Day” is a children’s word game: you play it by saying the opposite of what you mean: nothing has to change in the world, everything just becomes its opposite because you say so and you agree to believe it.

Recalling a workshop with students at the University of Victoria in As We Have Always Done, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson points out: “The opposite of dispossession is not possession.”[5] Reading this, I thought of how we seem to play Opposite Day without knowing it: the constant, tenuous game of language defining how we relate and how we know. And in whose language?

Opposite Day comes from my ongoing studying, which oscillates between thinking and doing: particularly through practising taijiquan (a Chinese internal martial art) as a way of understanding opposites as processual and relational. Simultaneously, I’ve been reading about separation, distinction, valuation in western philosophy, compared with Chinese practising~thinking of 道 dao (way). I return to the question of how language figures into these different modes of thought; the west’s preoccupation with articulability and positivist clarity, the Chinese leaning towards ineffability, negation, and silence. There’s this story in 莊子 Zhuangzi describing words as a fishnet; they are tools to capture meaning but you can forget the fishnet when you have the fish.[6]

Through reading, I have been in conversation with what we call ‘daoist’ classics: 莊子 Zhuangzi and 道德經 Dao De Jing. All studying is, in some way, a conversation. I wanted to take this reading-as-studying into dialogue with others, to bring these several thousand year old texts into this COVID-fractured globalized present, to play with the thoughts and questions with others through a series of sustained conversations. By keeping the textual study close to embodied study, our dialogue was always also through haptic registers that would loosen the form of conversation itself.

The relationships formed over time through various shared activities, encounters that would resonate from one moment, one person, to another, weaving together as I would braid traces of them into each other.

In order to play Opposite Day, whatever you want to name you must first know its opposite. What determines an opposite? What if you can’t name it? How to approach unknown unknowns: through language or not? How to stay with this levity of studying, of letting oneself sink into knowing, of playing, of ineffability? In our conversations, we muse that perhaps the opposite of an opposite is a movement back and forth, or being beside.

To trace dao (ways) without the safety net of a system of belief, it’s not “daoism” but to trace, like little rivers, how these ways are part of, can be part of, how we study here and now, and how we might perceive that study renewing us, renewing things.

Toleen:

Many of your projects are based on collaborations.. In my work, which is almost always collaborative as well, I often think of the intricate details of collaborating with others that are not only about the nature of the project, but the nature of our relationship – how conversation builds, how ideas develop, how personalities click, or not, how understanding flows, etc., and how that feeds into the nature of the work. I guess one thing to think about is: what’s visible from the nature of the collaboration in the project/exhibition/documentation?

Serena:

Working with others is double-layered: paying attention to what you’re doing and how you’re doing it. When you start to work together, you might ask, “How do you like to work? What’s your mode of collaboration?” To even ask the question directly like that, super pragmatically in my North American English, what does that presuppose – that we can articulate the how of working, when it’s like…we kind of know how we work. So talking about “how to work” – what can that do, beyond just figuring it out by working together?

Toleen:

Things happen, right? Things develop organically. But then if there’s a problem, or if there’s a conflict, it’s hard to deal with because you’ve never talked about it. Things are kind of “out there.”

Serena:

The how is to just build up a relationship: giving something time and space means that you pick up on those things. You don’t actually need to articulate it. But what it requires is a reciprocity of reading: Like, are you reading what the other person’s giving you? And are you expecting them to read into what you are giving them, that you might not even be aware of? For me, this always comes back to the choreography of restaurant or manual labour jobs – the energy or flow that comes from anticipating each other’s needs within a certain space and time.

Toleen:

Doing versus articulating or feeling things versus articulating them. I’ve often felt that the work that I do in Jordan, like Spring Sessions for example, is much about doing, doing, doing.[7] Whereas here (in Toronto) I feel like there’s a lot of attention paid to articulation, there is a lot of thinking around language, but it doesn’t necessarily correspond to doing. There’s a lot of language and documenting and positioning things, like it could survive just in the realm of language without necessarily enacting or embodying things.

Serena:

Exactly. And I mean, that’s the crux of what I was trying to have inform the methodology of Opposite Day, without it actually overtly informing it. Because the way I related to everyone individually was in response to who we are as individuals, and like, what kind of relationship we have. So there wasn’t an overarching “This is the ‘cookie cutter’ for all of our relating.”

The Study Partners are mostly folks I met recently, around 2019. I was interested in how they work; most I have known as friends or colleagues, and a couple I’ve known for many years and have collaborated with before. I’d gotten a sense from each of them that they have some affinity with play in how they work – that they would be open to studying with me by playing with unknown unknowns, and through embodied practice. The embodied-ness comes through different things: dance, sculpture, music performance, a medical condition, meditation, poetry. They come from different places: Toronto via Pakistan, China; the UK; Indonesia via The Netherlands, the Netherlands via Indonesia; Vienna via Kazakhstan, and via France. We meet in various rooms online, various parks, various studios, various grounds.

The format for Opposite Day comes out of various conversation-based things I’d been doing over the years, particularly Doing the dishes: a series of visits to single moms or daughters of single moms, where I would meet them in their kitchens and wash their dishes and we would talk from that point of shared experience as moms and/or daughters. The axle connecting the radiating spokes of these visits was my ongoing conversation with Christina Battle, a close friend and collaborator who was curating this as a project; we would talk in her car as she drove me to or picked me up from a visit. The lingering questions and weight of the energy of sharing experiences, and space and time of the dishwashing, was what coalesced in the moments of reflecting with Christina in the car, to and from somewhere. It was difficult to shape the dishwashing visits into a form that others could ‘enter’ as an artwork that didn’t render the experiences into ‘consumables’; ultimately the edge of the ‘artwork’ or ‘performance’ was a fuzzy gap. In the case of Opposite Day, a similar fuzzy gap is there around each of our study encounters, but the focal point of dishes is perhaps more defined in its obscurity: intimacy and confidentiality under a protective framework of single mom and/or daughter-ness; whereas Opposite Day contends with the time and pace of study, and the notion of an ‘outcome’ that is adjacent to the processual maintenance work of dishes.

The Study Encounters suggest a spectrum of object~processes for ‘defining’ collaboration and knowledge production. Some Study Partners were concerned about “what we were supposed to be doing,” what the outcome should be. For other Study Partners, the ‘outcome’ was something I consciously told myself to leave aside when meeting them, because they didn’t need to know, didn’t ask about.

Toleen:

What’s been happening with your study partners since the project started? Have relationships evolved, changed or died down?

Serena:

The relationships are ongoing but now there just isn’t such an urgency or regularity of structure in meeting with them. That moment, bracketed as a ‘project’, was about building up new modes of sensitivity and attunement, learning new ways of noticing.

Toleen:

It’s nice to let these things rest for a bit, right? Then they’ll come back somehow, in their own way.

Serena:

Yeah. This attenuation to just being receptive to certain things, or being able to put certain things together…to put things side by side, but not try to force a meaning out of it. Because I feel like, in this range of conversations and the range of comfort or discomfort that people have with things having a point or not having a point. Or there being the centrepiece to the meal, the roast goose in the center of the table, and everything else is a side dish, you know, how people want it like that, or whether or not people want to eat, like, dim sum style, right? Like, “Oh, what’s here? Oh, that looks fine. Yeah, let’s have a bit of that! Oh, we need some more tea to balance this out,” you know? There’s no centrepiece, it’s just whatever comes along and goes well together, you know?

Yeah, it’s also noticing in what parts of our lives do we expect there to be more direction? Expect there to be more articulation of a goal, or like, something to “get” from this? But also, conversely, sometimes you get so excited about an idea, or excited about a connection, and you just rush into it. And I find myself doing that a lot. I suppose it’s a very cerebral way of producing.

Toleen:

Yeah, this rush is exciting though; when you make this connection or feel a surge of energy and you rush into it. And then afterwards I guess you can take a step back from it and see it from a wider perspective and be like, Oh yeah, okay, chill. There’s this, but there’s also that. But there’s also that other thing! Like dim sum, right? There are many different varieties, and you can’t just have one kind. In the end, your circle back to the ones you liked the most.

Leo, on breathing

Leo, on breathing

Serena:

I don’t want to call anything an ‘exhibition’.

Toleen:

[rolling cigarette] Yeah, I’m curious: what is it about the term ‘exhibition’ that doesn’t satisfy you? I think for wave hands, like clouds, not eyes at Or Gallery in Vancouver you called the work a series of encounters, which was also curiously developing at the same time as Opposite Day.

Serena:

‘Exhibition’ is very cold, detached, it’s sort of pre-determined as an art framing, and I want to be inside this thing. I mean, it’s about internal processes. Yeah, I don’t know, a sort of turning inside out or something to be inside of, like an experience. So I keep saying ‘space’ instead of ‘exhibition.’

Toleen:

Exhibition seems to me to imply you putting objects on display, whereas space is more about the feeling you are trying to elicit in an environment. I also feel like it’s not just about it being this kind of internal space for the viewer though, it’s also part of your process of making the work.

Serena:

Yes…and I’m not so interested in interactions with art-as-exhibition, as representations. I think this is also a very fundamental thing in studying with an understanding of how these philosophies are not written about but are rather practised. The writings are indications of what is happening when you’re practising through embodied forms, so all of these forms of embodied study, they’re links to this thing, but you’re not going to pinpoint it to a concept. It’s not a dead butterfly pinned in a box way of “knowing” something: you’re always practising in order to try and grasp it by feeling it, and this is what aesthetics does. Like how Rolando Vazquez calls for decolonizing aesthetics as the means of reorganizing the senses: ethics in relation to how you order your senses – how you sense, how you know, how you relate.[8]

Toleen:

I remembered you as I was reading Imagining Water in the Anthropocene (Astrida Neimanis)[9] and particularly thought of water in your installations. She tries to theorize this concept of “bodies of water” as a way for us to relate to water; and as a way of thinking about environmental justice and ways to remedy our abuse of water. But also, “bodies of water” as in: we are made of water, everything is made of water. It’s interesting to think about that in terms of embodied practice and all of the things we were talking about with Opposite Day and your installation in Vancouver. So, what the Anthropocene does is that it selects certain qualities of water, and they become what water is. Water as an infinite resource, for example or “clean water.” Whereas she’s saying if we want to think of it as “bodies of water,” we need to select different qualities of water: like malleability, like the fact that it’s in so much of our bodies, its fluidity, gestational capacity, interconnectedness, and its flexibility, its ability to respond to what and how we make of it. Selecting these other qualities of water and amplifying those in order for us to then be better with water.

Serena:

I think that, in what Neimanis writes about in terms of this ontologic of water, of amniotics, like for all those watery qualities, she’s articulating what is understood in 陰陽 yin yang cosmology – I think she calls it an “open-closed loop” – this interplay between yin yang; fundamentally, there is nothing outside of it. It is a closed-open loop. It’s not that it is everything as a fixed totality, but that it’s constantly changing. So everything is always just a manifestation, however long that takes. Some are quick, some take ages – but like whatever, because what is time – but they’re all just manifestations of something congealing and something diffusing, right? It’s just those opposites, that are paradoxically the same thing.

So with Opposite Day, I was trying to trace how we make and perceive distinctions, recognizing that they are also not distinct. They are ‘made distinct’ through words, but this is only a certain kind of ‘sense.’ So what do you do? How do you treat each other – how do we treat things – with this in mind?

Toleen:

What do we do with this in practice? Like, not in theory.

Serena:

Yeah, I think that through these conversations, and why I don’t want to call things ‘exhibitions’, I’m finding that it’s about the operation of noticing: we do all of these things in order to notice; a question of how to notice.

“We have no Art, we try to do everything well,” Balinese saying as quoted by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Manifesto! Maintenance Art, 1969

Alix, after reiki

Alix, after reiki

Toleen:

I think you once said, “all reading is extractive.”

Serena:

[laughs] I probably did… these days, as I’m trying to get close to Chinese writing, I just repeat and repeat to memorize the shapes and sounds; copy it out… It’s just sitting with the texts, and writing, and reading, and digesting; to consider reading as eating.

Toleen:

This project of legibility … maybe it’s also about sitting with things, and not necessarily understanding everything. Thinking about doing versus articulating, or reading theory about something that is so unexplainable. I think it’s similar to our relationship with dreams, for example – do you do any readings or analysis, or do you just dream?

Serena:

Since I was in sixth grade, I’ve written down my dreams as much as possible. But no, I’ve never looked them up. I’ve never had any desire to, I don’t need them to mean anything. I just write them down so I can go back to that feeling of being there. Very often I draw architectural elements and describe spatial elements, trying to describe it so that I can revisit it.

Toleen:

Only in the pandemic did I start a dream journal. I wrote down my dreams randomly here and there throughout, but now I have one really long document that lists so many dreams. And it’s interesting, so many of my recollections are trying to describe the space. When I go back and read the dream journal, I’m always surprised to see patterns and repetition in spatial elements, as well as movement and feeling and characters. But also, in this quest of articulating things that are hard to grasp, I think for me, it’s not about making meaning out of them, but I think there’s something worthwhile in trying to describe things, like dreaming, in detail.

At the moment of writing, the dream is not material anymore, although it’s still with you and it was material when you were in it.

Serena:

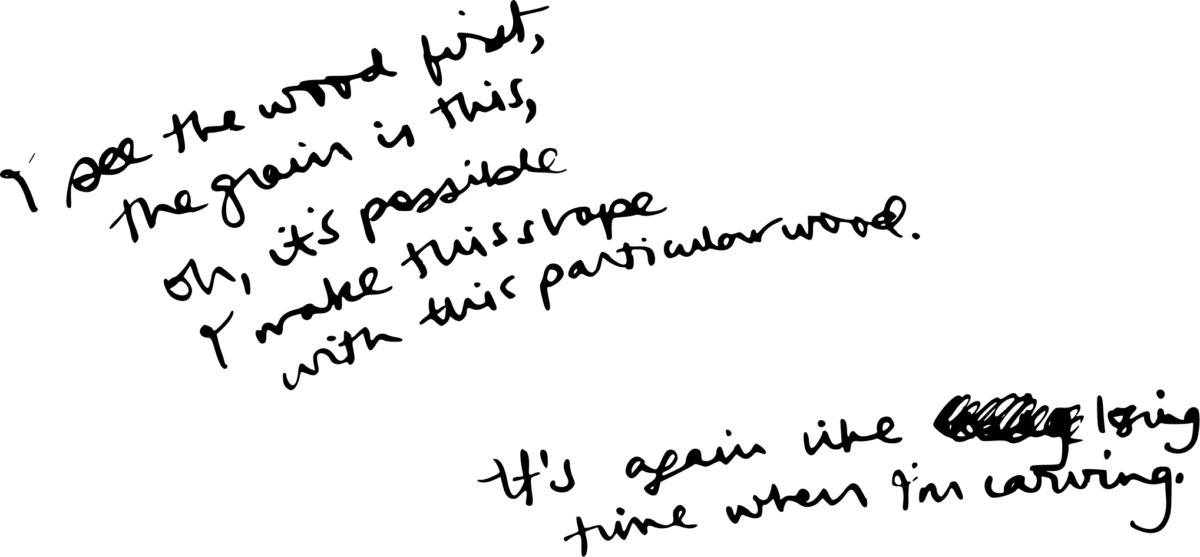

Yeah, it’s interesting to think about this as a body of writing that has no desire to make meaning of things and exists as description: it creates different readers. For me, it’s to go back to a feeling of being sure of a logic of something. There’s the Chinese word 理 li for ‘order’, in the sense of following the grain in wood, or vein in stone; an internal logic. When you’re experiencing the dream and something ridiculous happens, or someone says something, it’s like, this makes so much sense! I don’t even know what it means, but I love this feeling of conviction, being dropped back into that logic.

Toleen:

That’s so true. Waking up with this feeling of conviction is so real. But not being able to do anything with it, really, but can you carry it with you, so there’s actually much to do with it, as a sensibility.

Serena:

I was thinking about this in terms of the piano, there’s this internal logic of playing a song: its tonal structure, harmonic narrative, and this sense of resolution that are part of the canon of European/western cultural imperialism. But playing allows me to loosen up what my mind is doing, that double-bind, because my mind, my eyes, my ears, my hands are occupied. So then all these other critical thoughts go off in a different direction and you don’t make those distinctions, and there’s just the logic of the song. In a way, it’s like the logic of a dream, where you don’t get stuck in contradictions. It’s not that they don’t exist and you don’t fully let go, but it’s a way of letting go while being aware of the contradictions.

Toleen:

Yeah, it’s, again, just being with the thing and sitting with the thing, and not having to make meaning out of it.

Serena:

It’s funny because you just can’t talk about music. You can, of course, but there’s also no point in talking about it, which is wonderful. I feel like visual art has unfortunately gotten away from that. It always seems like you can talk about it.

Toleen:

Do you miss the idea that there’s no point in talking about art, or not having to talk about it?

Serena:

I don’t even know if it’s a matter of missing it, because I don’t know if I’ve ever actually experienced that. Words are such a prerequisite with visual art, as a ‘discipline,’ which is why I think performing has always been interesting to me.

Toleen:

Because you’re just doing it.

Serena:

Yeah, and this came up in another conversation yesterday: even if you don’t share the same embodied vocabulary – like if you’re watching someone carve something – you could be thinking of it in terms of martial arts; or you’re watching someone sew something: it activates a certain material embodied understanding of that thing. And you might not share all the skills and training of that person, but you can get into it. And I think that that sort of prehension – of any sort – is what lets you enter another’s experience; the performing allows you to notice. It’s not about empathizing with their subjectivity… And by ‘perform’ I just mean, like, do a thing.

After our conversation, I’m gonna have an exercise session with my dad.

Toleen:

And what happens when you’re practising with your father?

Serena:

Oh, it’s a model for me. I’m learning. I’m learning from watching him. Watching my dad and seeing how he watches how things are done… it was always him doing karate, and watching skaters and swimmers during the Olympics, and now it’s also how he watches rhumba, waltz. He watches movement; he watches by moving. He finds the grain of things, in different things. It’s that same kind of jumping into an internal logic that just feels right somehow. And that, I don’t think you need to talk about. Hmm. To see someone else really sinking into it. I just learn so much from others modelling things, just by getting a glimpse of how they sense the world.

Leo, on following

Leo, on following

How I describe our encounters, read by Study Partners during The opposite of an opposite on 17 November 2021.

To Leo, read by Sameer Farooq

We start with a haircut — we’ve just met and together, we cut the hair of our friend Jay, two pairs of scissors, working around each other, with each other.

We start by drawing and talking on screen. I draw with my non-dominant hand, to slow myself down, to surprise myself.We use ink, pencil crayon, graphite pencil, marker.

We look up occasionally, we don’t see what each other is drawing until at a certain point we hold it up to the camera, then we try to draw in the style of one another: your drawing gets more frenetic, my drawing gets calmer. We talk about sediment sinking in the water, the time it takes for things to sink, for knowledge to be something in the body, heavy and embedded, and not just a theory, a thing you read yesterday.

We try to figure out where your family is from, who speaks what dialect, who migrated where and when and why, we try to trace what we know, what we remember based on how far we are now from where we come from.

Sometimes we don’t speak and just look at what we’re drawing. A lot of light, pink strokes on pencil on the page. This is where we sat, silently making marks, because it was a difficult thing to say, and a difficult thing to respond to.

We move through taijiquan and look at passages of Zhuangzi and Dao De Jing when they come up in our conversation. We talk about desire, about simplicity, ‘su’ 素 — or cooking simply, without garlic and onions, which is not quite the opposite of minimalism; you tell me to watch the Jeong Kwan episode of Chef’s Table on Netflix, and we talk about how to live well, to live close to things, how you must take care of your tools as part of carving wood. We move through some taijiquan and talk about emptying, and how it’s not actually empty. We ask ‘how do you know what is enough?’

To Giles, read by Leonardiansyah Allenda

We start to write together again, this time, we decide to write a musical. It’s been years since I could hear your playlists through the wall, coming from your studio beside mine; now, you sit across from me on screen and show me the postcard-sized drawings you have been doing, in the spirit of quickness; the postcard drawing that you have made into a blanket.

For years, I have been amazed at how you do things quickly, by embracing bewilderment, doing through doing. We talk about how harmony works, I try to describe the theory of intervals, thirds and sixths, but can only put it in terms of listening and imagining and doing all at once.

I am reminded of ‘quickness’ as Calvino has described it, citing the story of the scholar in the ancient Chinese court, summoned to draw the perfect crab for the emperor, the brushstroke that took 50 years to cultivate, quickness that comes from slowness. Undercurrents that feed us. Something prompts you to re-send me photos that you had sent me years ago of juice boxes in a supermarket display, arranged as an airplane. Maybe it’s like the sediment that sinks at its own pace, the water that takes its time to become still; this clear water that Leo has talked about. In the Zhuangzi, it is written that only still water can be a mirror.

The So-Called Clock is the musical we are writing: we start with crossword puzzles from the Guardian, and we collect the words that escape us. We start with a shared list of words that we didn’t know. We sit across from each other, listening to the Golden Record and writing with words that we didn’t know, words which then become their opposites, which and we write from the opposites of the opposites. Not knowing and making, making from not knowing, and the words on the page have more space around them because they are written with music in mind, our musical that has yet to be written. We never determined what this was about — we just continue to make things across from each other, writing quickly and without second guessing.

To Fan, read by Giles Bailey

We had only met twice before, about a year ago, and this time we start immediately without small talk; we go straight to questions like, how can we act without intention, wu wei? What does it mean to come from somewhere? How can we do this practice when we are far from where it comes from, from where we come from? We walk through High Park and it’s often sweltering. One time, we got huge ice creams and yours melted copiously onto the ground; I was more strategic with my tongue.When we start, we do something like qi gong by the pond, but I rush through it, not trusting necessarily that you are actually interested. Then you guide us through some butoh exercises, and you take the time it needs. I learn that you trust the doing, so you set the tone in order to give the doing its time — not a representation or gesture of doing. And I follow you in this space you’ve made.

I ask you where your family is from, where your name is from; you help me decide my name by listening closely.

We start by writing our names: we practice writing, we sit at a neighbour’s dining table and scrawl with clumsy ink. By writing, we talk about the words we like, the words that are difficult, where they come from and the way those traces of bamboo, rain, movement, mouth, are present or absent in simplified and traditional script. We try to remember how things are written, piecing things together, we remember by writing, together.

We sit with notebooks and our phones, a book on our laps, we translate intuitively, mining the diasporic shards of what we can remember, looking at radicals that are familiar, three splashes of water or the sound that also means money: the image of a flash of feathers, a startled bird standing in water, words that follow movement instead of figures. We relish this, as much as we love talking, we leave space for this. As we fumble through translating, we don’t need to talk about making sense. On the opposing pages, our translated poems upside down facing one another.

To Alix, read by Fan Wu

We start by walking through the city centre, you tell me that sometimes you play at not holding onto anything on the tram so that you can practise balancing. This reminds me of my dad; using the bus stop and the bus as the space and time to practice in the margins that make up the day; the way you move through your everyday — there’s the dance, you don’t need to bring anything else.

When we walk on the dirt path, there are pauses that are both heavy and light, I learn the rhythm of how you take time to think, make a connection, and respond.

I hear you say that you have a lot of patience, and I understand this with certainty because of how you move, how you speak within your movement.

You walk with, walk through the path of the horse, instead of avoiding the piles of dung.

You hover over me, doing reiki in person; you notice the sky from the floor of my studio at Augasse. There is just a blue sky, from that angle of lying on the floor, and I never noticed it before because I have been upright. You say that there is no intention when you do the reiki treatment, you have no intention, it’s an amplification of whatever is already there. You tell me you are always learning when you do the reiki treatments, learning to notice what else is possible. The eyes don’t lead the movement.

You answered my email with: “let’s move through the metaphor” and I think your ‘through’ actually means ‘through’.

We move and talk, talk and move, sometimes you suddenly drop to touch the ground to finish your sentence. Sometimes you point with hand, toe, chin, sometimes the point that you voice shifts, as your breath changes with your movement.

We meet for reiki remotely: in Vienna, you create a version of my body out of books, a handknit scarf, drawings, a balloon, scribbled notes — anatomie éclatée. In Toronto, I lie on the floor and feel the different parts of my body take on different gravities, anatomie éclatée, a slowly exploding body that is simultaneously both separate and whole.

You send me a score for being a fountain and it is exactly when I need it.

To Sanne, read by Alix Eynaudi

We started to talk about studying for years now, since we were both in the Netherlands. We’ve been sharing ways of studying as we’ve navigated different levels of humidity, timezones and languages, working conditions. You fell ill and forgot most of what we had talked about, so we’d go back, repeat, rephrase, reconsider. You tell me about how it felt to lose emotion, all memory of an event, what it was like to lose your self in those moments. We leave each other voice messages, out of sync, our seasons and times of day, out of sync. Study that happens in the crevices of the rest of the day, your morning, my evening, and vice versa. Study that happens, like garnishes around the main dish. You poured coffee onto your laptop. Your laptop started to burn your hand.

Things that happen out of order, and when you say something about the in-between, I recall the re-telling of a story, a doctor talking to a patient who would carry crumpled paper balls in the pocket of their hospital gown, paper balls to throw down the hall way so as to break the unbearable smoothness. In anticipation of the unbearable smoothness that threatened to freeze them into a catatonic state. My taijiquan teacher says to elongate the in-between, that taijiquan is the in-between. And I tell you this in a voice message on the train, which I have to repeat because I didn’t press ‘record’ — this notion of blockage (which is translated from Chinese into English as ‘negative’) versus smoothness. ‘Negative’, meaning ‘static’; ‘blocked’, meaning ‘without movement’. The smoothness you mention, as the well-oiled production mechanism, is it a smoothness that blocks? That causes one to freeze, immobile? What is the opposite of blockage? What is the opposite of ‘Negative’? I wonder if you can describe how this feels, your body that has lived through these states, and your words that you are so good with, the control you no longer have, to recognize your self. And I recall when we were in the same city, maybe for the first and last time, arriving to your home, without you there, but feeling as if you had led me up the stairs and set a cup of hot tea down for me, the afternoon sun stretched across the room, the scent of lavender, and random flowers that you gathered from crevices along the canals.

To Ruthie, read by Sanne Oorthuizen

We had been talking about ‘playing’ and I tell you about a grade seven English test, when I purposely spelled every word incorrectly in order to receive the stamp of a turkey, signifying total failure. We started our study by walking along the island in the river, the park, the other park, and as the weather warmed, we decide to go to the Kunsthistorisches Museum for “structure”. Your forged press passes lead me to realize that, obviously, we must plan a museum heist. You are someone with a mission, but you confide in me that the mission is not clear to you. I have my people send instructions to your people. I open the dishwasher, I open an avocado, I open the water faucet, a clue hidden in a smudge of pistachio butter. My people shoot quickly, and without cutting, they send you short videos as coded instructions for our heist. I don’t know what they mean either. We go to the museum to interpret. Our tools for interpretation need to be interpreted by each other. You bring marbles and bananas. I bring mirrors. Improvisation is a theory and a practice: in theory, we will only observe the museum through mirrors. In practice, we bump into the hedge of not-knowing, a wall that reveals that we never left the labyrinth, the edges are still there to contain us. We return to the question of how to live with uncertainty, how much unknown can be left unknown. We go to the Weltmuseum on a Wednesday, the only day of the week when the museum isn’t open, and lock down will start the next day. So instead, we go to Stadtpark and sit on the grass, talking about expectations and art production. Where do playing, knowing, and emptying sit in relation to one another? You ask me what I mean by ‘duality’ and I tell you about my dad’s explanation of why you have to keep your tongue touching the roof of your mouth when you’re doing qi gong — “Why? Because you can feel it… the current of energy circulating. If you don’t have your tongue touching the roof of your mouth, the circuit is broken. You can feel it.”

To Sameer, read by Ruthia Jenrbekova

We start on the floor, you in Toronto and me in Vienna, we start with a recording of your voice, guiding us into a sinking feeling, the feeling of our bodies sinking into the ground. You guide us through surfaces, a ball or a cube that grows, that is within us, that engulfs us, you tell us to pay attention to the textures. When we are sitting again, describing the visualizations, we talk about how we use language for this, how we shape our words around things that we may or may not have seen. I listen to your vivid descriptions, how you follow, through practicing, certain forms transforming into and relating to others. I scrape and dig for a vocabulary I lack to describe things I’m not sure I’m feeling and seeing. And when we say ’emptying’ is this how it feels?

We talk about intention, we talk through intention, and later in the summer, I will think about this when Fan and I practice being insensible objects, and then slowly noticing our limbs as if for the first time.

At the edge of the Junction, we stand at a street corner and talk about the names we were given and the names we chose, that we continue to choose. We bounce between the slivers of different languages that we share, always punctuated with a laugh.

At the edge of your garden, we look at my drawings and you ask me what is it I want others to feel, and what that means as a commitment to materials.

We start with lunch, and I watch you gently layer flavours and textures in the kitchen of a friendly ghost.

We start on the floor of the stone terrace at the edge of lake and sky, at the edge of summer. A voice guides us through movement and even with our eyes closed we squint, lying on our backs, facing the full sun. Then we stand at the ground’s edge over the water, and feel our hands rise as we sink. Afterwards, you tell me that your mind was so focused on the small things happening in your body, that there was no mind left to go wandering. We talk about the difficulty of representing what we’ve seen, the difficulty of making things into objects. We try to imagine ‘position’ as a moving-through instead of a fixed coordinate, instead of something to ‘take’.

Endnotes

[1] Lorde, A. (1984). The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. In Sister outsider: Essays and speeches (pp. 110–114). essay, Crossing Press.

[2] Fielding, H., Olkowski, D., & Manning, D. T. (2017). The Murmuration of Birds: An Anishinaabe Ontology of Mnidoo-Worldbuilding. In Feminist Phenomenology Futures (pp. 154–182). essay, Indiana University Press.

[3] Jullien, F. (2015). Book of Beginnings. (J. Gladding, Trans.). Yale University Press.

[4] Lee, S. (2021-2022). wave hands, like clouds, not eyes. Exhibited at OR Gallery, Vancouver October 22 – January 22 2022.

[5] Simpson, L. B. (2019). As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance. W. Ross MacDonald School Resource Services Library.

[6] Zhuangzi. (2013). External Things. In B. Watson (Trans.), The Complete Works of Zhuangzi (pp. 227–233). essay, Columbia University Press.

[7] Al Khasawneh, N., & Touq, T. (2014). 2019 Edition. Spring Sessions. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from http://www.springsessions.org/

[8] Zhuangzi. (2013). External Things. In B. Watson (Trans.), The Complete Works of Zhuangzi (pp. 227–233). essay, Columbia University Press.

[9] Neimanis, A. (2019). Imagining Water in the Anthropocene. In Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology(pp. 153–185). essay, Bloomsbury Academic.

Readings

Xiang ZaiRong

Zhuang Zi (translation: Burton Watson)

Astrida Neimanis

David Abram

Sylvia Wynter

Mel Y. Chen

The opposite of an opposite

Artist

Serena Lee

Serena Lee’s practice stems from a fascination with polyphony as a way of mapping how things come together and apart. She plays with movement, language, cinema, textures, space, and voice, tracing embodied knowledge through aesthetic, martial, and sonic practices. Ongoing collective study includes collaborating with Christina Battle as SHATTERED MOON ALLIANCE, a DIY framework for sci-fi world-building; and with Read-in, collectively researching political, embodied, and situated practices of reading. Born and raised in tkaronto/Toronto, Serena is currently based in Vienna where she is doing a PhD at the Akademie der bildenden künste Wien (AT); she practises close to home and internationally.

Contributors

Fan Wu

Sanne Oorthuizen